A lot of parenting books talk about the value of consistency in parenting – when you are consistent with your approach with something, the theory goes, the child knows what to expect, and so is less anxious about what will happen.

It is not just about children – when something is more deterministic, you can “take it for granted” more. And that means less anxiety about it.

From another realm, prices of options always have “positive vega” – the higher the market volatility, the more the price of the option. Thinking about it another way, the more the uncertainty, the more people are willing to pay to hedge against it. In other words, higher uncertainty means more anxiety.

However, sometimes the equation can get flipped. Let us take the case of water supply in my apartment. We have both a tap water connection and a borewell, so historically, water supply has been fairly consistent. For the longest time, we didn’t bother thinking about the pressure of water in the taps.

And then one day in the beginning of this year the water suddenly stopped. We had an inkling of it that morning as the water in the taps inexplicably slowed down, and so stored a couple of buckets until it ground to a complete halt later that day.

It turned out that our water pump, which is way deep inside the earth (near the water table) was broken, so it took a day to fix.

Following that, we have become more cognisant of the water pressure in the pipes. If the water pressure goes down for a bit, the memory of the day when the motor conked is fresh, and we start worrying that the water will suddenly stop. I’ve panicked at least a couple of times wondering if the water will stop.

However, after this happened a few times over the last few months I’m more comfortable. I now know that fluctuation of water pressure in the tap is variable. When I’m showering at the same time as my downstairs neighbour (I’m guessing), the water pressure will be lower. Sometimes the level of water in the tank is just above the level required for the pump to switch on. Then again the pressure is lower. And so forth.

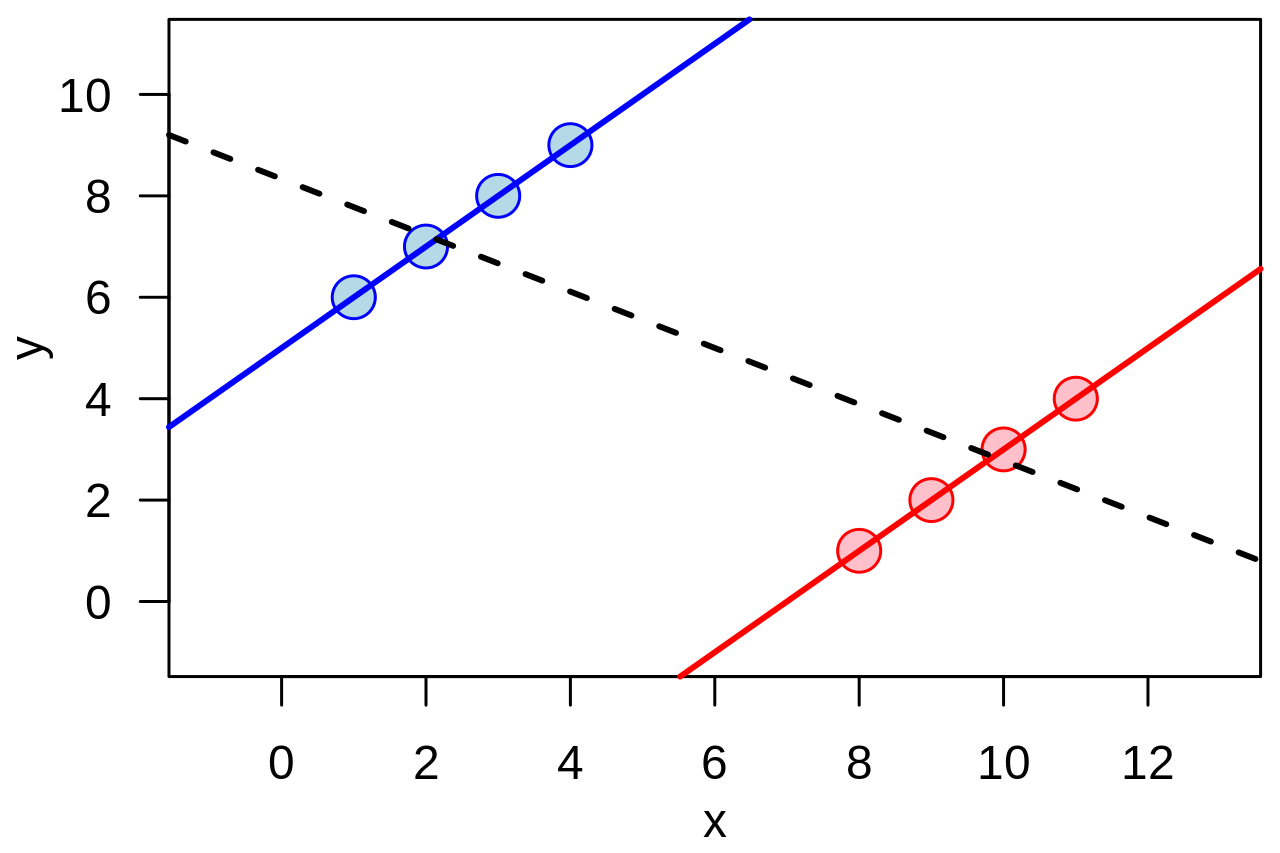

In other words, observing a moderate level of uncertainty has actually made me more comfortable now and reduced my anxiety – within some limits, I know that some fluctuation is “normal”. This uncertainty is more than what I observed earlier, so in other words, increased (perceived) uncertainty has actually reduced anxiety.

One way I think of it is in terms of hidden risks – when you see moderate fluctuations, you know that fluctuations exist and that you don’t need to get stressed around them. So your anxiety is lower. However, if you’ve gone a very long time with no fluctuation at all, then you are concerned that there are hidden risks that you have not experienced yet.

So when the water pressure in the taps has been completely consistent, then any deviation is a very strong (Bayesian) sign that something is wrong. And that increases anxiety.