At about 5:30 pm last Wednesday, I chanced upon a box of Sandesh crumbs lying in the office. A colleague had brought the sweets to share the previous day, and people had devoured it; but left aside the crumbs. I picked up the box and proceeded to demolish it as I reviewed a teammate’s work.

Soon the box was in the dustbin. I chanced upon a cookie box that another colleague had got. And started to demolish the cookies. This was highly atypical behaviour for me, since I’m trying to follow a low-carb diet. At the moment, I assumed it was because I was stressed that day.

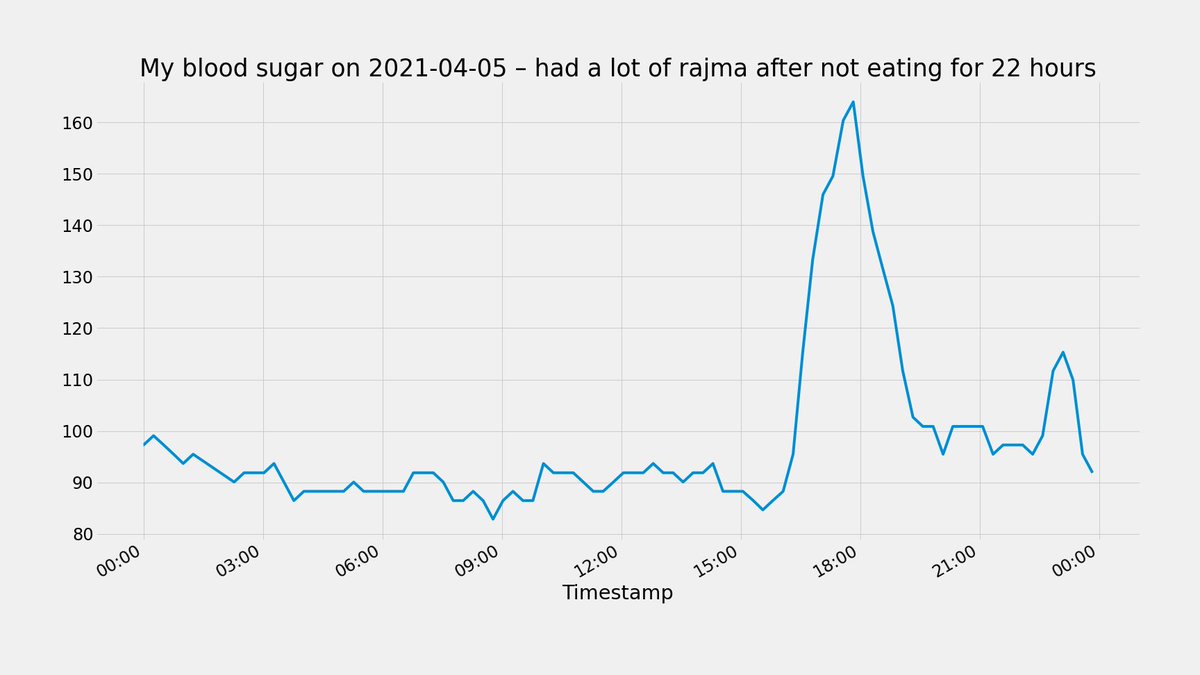

Presently, I took out my phone to log this “meal” in the Ultrahuman app. There the reason for my binge was clearly visible – my blood sugar had gone down to 68 mg / dL, pretty much my lowest low in the 2 weeks I wore the last sensor.

This, I realised, was a consequence of the day’s lunch, at Sodabottleopenerwala. Maybe it was the batter (or more likely, the sauce) of the fried chicken wings. Or the batter of the onion pakoda. Something I had eaten that afternoon had spiked my blood sugar high enough to trigger a massive insulin response. And that insulin, having acted upon my lunch, had acted upon the rest of the sugars in my blood. Sending it really low. To a point where I was gorging on whatever sweets I could find.

About a year (or maybe two?) back, I had read Jason Fung’s The Obesity Code, which had talked about insulin being the hormone responsible for weight gain. High levels of insulin in the blood means you feel hungrier and you gorge more, or something like that the argument went. The answer was to not keep triggering insulin release in the blood – for that would make the body “insulin resistant” (so you need more insulin than usual to take care of a particular amount of blood sugar). Which can lead to Type 2 diabetes, high triglycerides, weight gain, etc.

About a year (or maybe two?) back, I had read Jason Fung’s The Obesity Code, which had talked about insulin being the hormone responsible for weight gain. High levels of insulin in the blood means you feel hungrier and you gorge more, or something like that the argument went. The answer was to not keep triggering insulin release in the blood – for that would make the body “insulin resistant” (so you need more insulin than usual to take care of a particular amount of blood sugar). Which can lead to Type 2 diabetes, high triglycerides, weight gain, etc.

And so Fung’s recommendations (paraphrasing – you should see my full blogpost based on the book ) included fasting, and eating fewer carbs. Here I was, two years later, finding evidence of the concepts in my CGM data.

I have worn a CGM a couple of times before. Those were primarily to figure out my body’s response to different kinds of foods, and find out what I should eat to maintain a healthy blood sugar level. The insights had been fairly clear. However, since it had been ten months since I last wore a CGM, I had forgotten some of the insights. I was “cheating” (eating what I wasn’t supposed to eat) too much. And my blood sugar had started going up to scary levels.

The objective of this round of the CGM was to find out “high ROI foods”. Foods that gave me a lot of “satisfaction” while not triggering much of a blood glucose response. The specific hypothesis I was trying to test was that sweets and traditional south indian lunch trigger my blood sugar in the same manner, so I might as well have dessert instead of traditional south indian lunches!

Two weeks of this CGM and I rejected this hypothesis. I had sweets enough number of times (kalakand, sandesh, corner house cake fudge, etc) to notice that the glucose response was not scary at all. The problem, each time, however, occurred later – maybe the “density of sugars” in the sweets triggered off too much of an insulin response, leading to a glucose crash (and low glucose levels at the end of it).

Traditional south indian lunch (I would start with the vegetables before I moved on to rice with sambar and then rice with curd) was something I tested multiple times. And it’s not funny how much the response varied – a couple of times, my blood glucose went up very high (160 etc.). A couple of times there was a minimal impact on my blood glucose. It was all over the place. That said, given the ease of preparation, it is something I’m not cutting out.

What I’m cutting out is pretty much anything that involves “pulverised grains”. Those just don’t work for me. Two times I had dosa – once it sent my blood sugar beyond 200, once beyond 180. One idli with vade sent my blood sugar from 80 to 140 (on the other hand, khara bath (uppit) with vaDe only sent it to 120). Paneer paratha (on the streets of Gurgaon) sent my sugar up to 200.

That some flours work for me I had established in previous iterations wearing the CGM – rice rotti hadn’t worked, jowar rotti hadn’t worked, ragi mudde had been especially bad. But that dose and idli and paratha also don’t work for me was an interesting observation this time. I guess I’ll be eating much less of these.

What did work for me was what has sort of become my usual meals when going out of late – avoiding carbs. One Wednesday, I got my team to order me an entire Paneer Butter Masala for lunch (Gurgaon again). Minimal change in glucose levels. That Friday, I had butter chicken (only; no bread or rice with it). Minimal change yet again! Omelettes simply don’t register on my blood sugar levels (even with generous amounts of cheese).

Yesterday I had masaldose for lunch. To “experiment” what it does to my body. Absolute insanity.

This was at Konark (residency road) but I suspect all masaldoses wil have this effect on me. Basically Jai. pic.twitter.com/PnRqbOQxp4

— Karthik S (@karthiks) November 1, 2022

To summarise,

- Sweets may not send my sugar very high, but in due course they send it very low (due to high insulin response). The only time this crash doesn’t happen is if I’ve had the sweets at the end of a meal. Basically, avoid.

- Any kinds of pulverised grains (dosa, idli, rotti, paratha) is not good for me. Avoid again

- The same food can have very different response at different times. This could be due to the pre-existing levels of insulin in the body. So any data analysis (I plan to do it) needs to be done very carefully

- On a couple of occasions I found artificial sweeteners (like those in my whey protein) causing a glucose crash – maybe they get the body to release insulin despite not having sugars. Avoid again.

- Again last week I met a friend for dinner and we had humongous amounts of seafood. I didn’t eat carbs with it. Minimal spike.

- Some foods cause an immediate spike. Some cause a delayed spike. Some cause a crash.

- Crashes in glucose levels (usually 1-2 hours after a massively insulin-triggering meal) were massively correlated with me feeling low and jittery and unable to focus. It didn’t matter how recently I had taken the last dose of my ADHD medication – glucose crash meant I was unable to focus.

- Milk is not as good for me as I thought. It does produce a spike (and crash), especially when I’m drinking on an empty stomach

- Speaking of drinking, minimal impact from alcohols such as whiskey or wine. I didn’t test beer (I know it’s not good)

- Biryani (Nagarjuna) wasn’t so bad – again it was important I ate very little rice and lots of chicken (ordered sides)

- Just omelette is great. Omelette with a slice of toast not so.

All these notes are for myself. Any benefit you get from this is only a bonus.