Last weekend I finished off Jason Fung’s The Complete Guide to Fasting. Like his earlier book that I read (The Obesity Code), this book makes a very compelling case to fast as a means of reversing type 2 diabetes, lose weight and generally have a much better life.

I’m compelled enough by the book to have put its message into practice immediately. Apart from days when I go to the gym early in the morning, I’ve been making it a point to not eat breakfast (this isn’t the first time I’m trying this, I must mention). And while the weighing scales haven’t moved yet, I’m pretty happy.

In any case, in both his books, one thing that Fung rails against is the conventional medical practice of telling people suffering from Type 2 Diabetes to “eat 6 meals a day”, while most medical research shows that this leads to higher insulin resistance (and thus worse diabetes), and that what is better is to eat a smaller number of meals in a day.

So a few days ago, I came across this tweetstorm by this guy who installed a continuous glucose monitor in his blood. The tweetstorm is very instructive.

Finished a 14 day experiment with a continuous glucose monitor in my arm. Learnt a lot about how my body reacts to food!

?w graphs below. May be useful for folks with high blood sugar

All food in this thread was home cooked. I wrote some python to extract & clean the data pic.twitter.com/VwC9W5ZMoL

— Rishabh Srivastava (@rishdotblog) April 14, 2021

And this helped explain to me why despite research showing the contrary, eating “several meals a day” has been part of the treatment manual for diabetes, even if in reality (as per Fung’s book), it hasn’t helped.

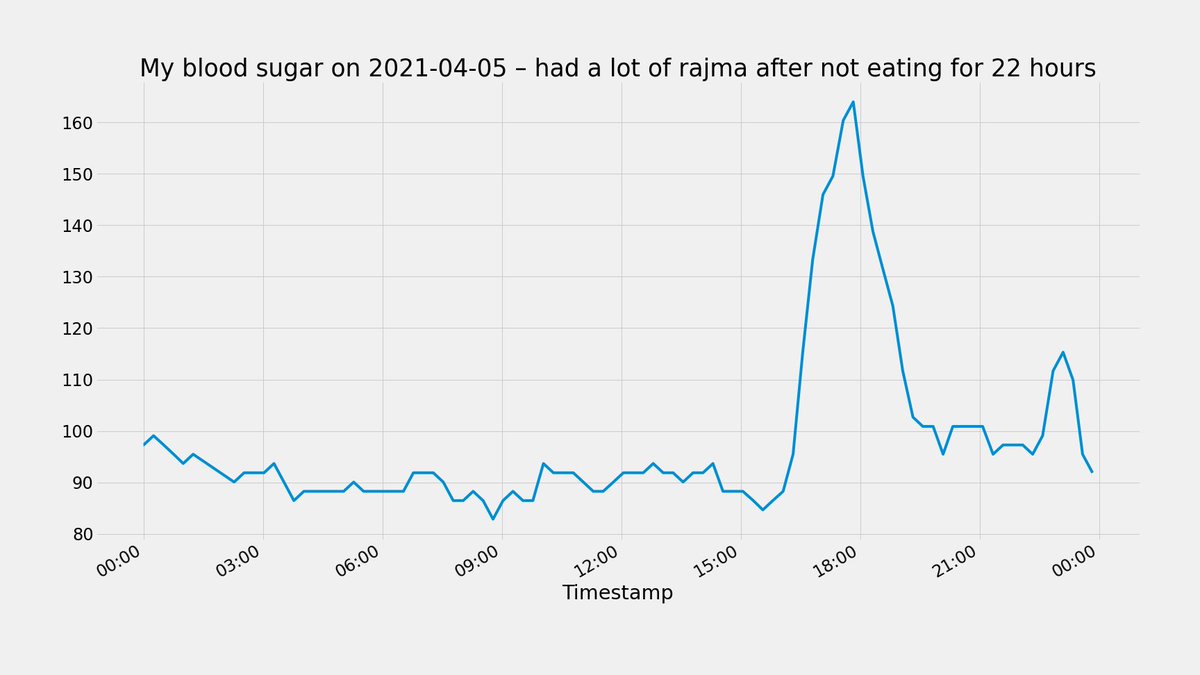

This graph from the tweetstorm is instructive:

Look at how his blood glucose spiked immediately after a meal that he ate after a longish fast. The conventional medical wisdom has been that if a diabetic eats infrequently, every meal will spike his blood glucose, which then leads to a spike in insulin, and that is not good for the person.

Instead, the wisdom goes (I’m guessing here) that if you have several small meals, then you don’t have a single big jump in glucose levels like this. And so you don’t have single big jumps in insulin levels.

Moreover, the big risk with Type 2 diabetes is hypoglycemia – where your blood sugar drops to such a low level that you start sweating rapidly and come under the risk of a heart attack. And when you don’t eat frequently, your blood sugar can drop like crazy. And so several small meals works.

Logical right? I guess that’s what most doctors have been thinking over time.

The little problem, of course, is that if you eat too many meals (and small meals at that), your blood glucose doesn’t spike by a lot at any one point in time. However, that you haven’t given sufficient gap in your meals means that your insulin levels never drop below a point. And that means that your body becomes resistant to insulin. Which means your diabetes becomes worse.

So what do you do? How do you let your insulin level drop to an extent where your body is not resistant to it, while also making the spike in insulin when you finally eat not so much? Again, I’m NOT a medical professional, but seems like what you eat matters – fat spikes insulin much less than carbs or protein.

Maybe I should change the nature of my lunch on days I don’t eat breakfast.

PS: This entire blogpost is entirely my conjecture, and none of it is to be taken as any kind of medical opinion.