This is yet another of those posts that elaborates something I’ve put on twitter.

Some 10-15 years back I thought I was interested in public policy. Now I've lost all interest.

Sincere thanks to @TakshashilaInst and @acorn for allowing me to explore this interest in a low-cost manner (as a part-time "resident quant")

— Karthik S (@karthiks) August 19, 2020

I remember getting interested in public policy sometime in 2005. I think that was around the time when I stopped solely talking about gossip (and random “life issues”) on this blog, and started commenting about random “issues” here.

That was also the time when Madman Aadisht introduced me to his blog circle that he called the “libertarian cartel”. Reading blogposts by this cartel (included the likes of Ravikiran Rao, Amit Varma, Gaurav Sabnis (who was once a libertarian), Nitin Pai, etc.), I was hooked. I too wanted in on this “libertarian cartel”.

Soon enough, I started work and did one project that involved the study of some economic reforms. I soon quit that job but wrote about this, and other issues. I started getting into the “econ blogosphere”. Between the libertarian cartel, the opinion pages of the Business Standard (back when TN Ninan was the editor) and “econ blogs” (the likes of Marginal Revolution and EconLog), I got deeply interested in “policy issues”. And I thought I wanted to do public policy.

Of course, what public policy pays is nothing comparable to what post-MBA jobs pay, so I never explored it seriously as a career. I kept moving from one highly paid job to another, though I kept writing about “policy issues” on this blog, and then on Twitter (when I opened an account there in 2008). I even wrote on the “Indian Economy Blog”. And while the libertarian cartel never admitted me as a member, when they did form a mailing list, I got invited to join it soon enough (thanks to Aadisht once again).

“Policy work”, or “policy blogging” (which might be a more accurate term), in the late noughties was enjoyable because most people (at least those I bothered to read) were issue driven. So you had the aforementioned libertarians who analysed issues through a libertarian lens. You had leftists like the Jagadguru Krish and “Jihvaa”. You had right wingers like SandeepWeb. Each class largely evaluated each issue based on their own philosophies, and commented about them. People avoided being partisan.

And so, in 2011, when I quit full time employment and decided to lead a portfolio life, I decided that public policy should be part of my portfolio. And the Takshashila Institution was kind enough to appoint me as its “resident quant” (for the most part, there were no formal responsibilities for the role and I wasn’t paid. However, we mutually enjoyed it, I would like to think).

That was a fantastic opportunity. I didn’t have to commit that much time, but got the optionality to participate in a large number of fairly interesting discussions with fairly interesting people. I did some work here and there, doing some research and teaching and course designing and lecturing, and it was most enjoyable. More enjoyable, of course, was the set of people I met through this assignment.

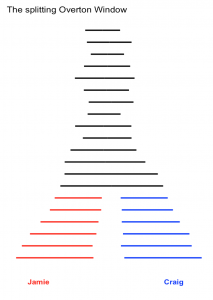

Somewhere down the line, maybe in 2015 or 2016 (or maybe even earlier), things changed. Basically policy became partisan. Out went the libertarians and totalitarians and right wingers and left wingers. In came the “Congressis” and “bhakts”, and republicans and democrats.

Output of policy analysis everywhere, except in academic journals (which I can’t comment on since I don’t bother reading them), became a function of the author’s political preferences. One year, an author might be favourable to the BJP and everything he/she wrote would nicely tally with the BJP’s view of the world. And then maybe the author would change political preferences, and there was a 180 degree turn on most issues!

On twitter, on mainstream media, on blogs, even on Instagram – “policy analysis” became rather predictable. Once you knew a person’s political preferences and leanings, it became clear what their view on any topic would be – it was identical to the view of their chosen party at that point in time. This partisanship meant there was “no information content” in any of this writing.

And that is how I started getting disillusioned. And the disillusionment grew over time, until a point when I started actively avoiding policy discussions (I’ve even muted the word “policy” on twitter).

I’m happy living my life, and doing my work, and earning my money, and paying my taxes. In the spirit of 2020, I’ll “leave public policy to the experts”.