I’ve written here a few times about the concept of “returns to experience“. Basically, in some fields such as finance, the “returns to experience” is rather high. Irrespective of what you have studied or where, how long you have continuously been in the industry and what you have been doing has a bigger impact on your performance than your way of thinking or education.

In other domains, returns to experience is far less. After a few years in the profession, you would have learnt all you had to, and working longer in the job will not necessarily make you better at it. And so you see that the average 15 years experience people are not that much better than the average 10 years experience people, and so you see salaries stagnating as careers progress.

While I have spoken about returns to experience, till date, I hadn’t bothered to figure out why returns to experience is a thing in some, and only some, professions. And then I came across this tweetstorm that seeks to explain it.

Now, normally I have a policy of not reading tweetstorms longer than six tweets, but here it was well worth it.

1/ Let's talk about how note taking can help you accelerate expertise.

Yes, I know how that sounds like.

No, this isn't hype.

There's some solid cognitive science here, and it has FASCINATING things to say about the nature of learning in messy, real world domains.

— Cedric Chin (@ejames_c) February 9, 2022

It draws upon a concept called “cognitive flexibility theory”.

Basically, there are two kinds of professions – well-structured and ill-structured. To quickly summarise the tweetstorm, well-structured professions have the same problems again and again, and there are clear patterns. And in these professions, first principles are good to reason out most things, and solve most problems. And so the way you learn it is by learning concepts and theories and solving a few problems.

In ill-structured domains (eg. business or medicine), the concepts are largely the same but the way the concepts manifest in different cases are vastly different. As a consequence, just knowing the theories or fundamentals is not sufficient in being able to understand most cases, each of which is idiosyncratic.

Instead, study in these professions comes from “studying cases”. Business and medicine schools are classic examples of this. The idea with solving lots of cases is NOT that you can see the same patterns in a new case that you see, but that having seen lots of cases, you might be able to reason HOW to approach a new case that comes your way (and the way you approach it is very likely novel).

Picking up from the tweetstorm once again:

12/ So what does CFT tell us?

CFT tells us that in ill-structured domains, concepts are hugely variable so reasoning from concepts are insanely hard.

In fact, extracting generalisable principles from case studies is close to impossible!

— Cedric Chin (@ejames_c) February 9, 2022

It is not hard to see that when the problems are ill-structured or “wicked”, the more the cases you have seen in your life, the better placed you are to attack the problem. Naturally, assuming you continue to learn from each incremental case you see, the returns to experience in such professions is high.

In securities trading, for example, the market takes very many forms, and irrespective of what chartists will tell you, patterns seldom repeat. The concepts are the same, however. Hence, you treat each new trade as a “case” and try to learn from it. So returns to experience are high. And so when I tried to reenter the industry after 5 years away, I found it incredibly hard.

Chess, on the other hand, is well-structured. Yes, alpha zero might come and go, but a lot of the general principles simply remain.

Having read this tweetstorm, gobbled a large glass of wine and written this blogpost (so far), I’ve been thinking about my own profession – data science. My sense is that data science is an ill-structured profession where most practitioners pretend it is well-structured. And this is possibly because a significant proportion of practitioners come from academia.

I keep telling people about my first brush with what can now be called data science – I was asked to build a model to forecast demand for air cargo (2006-7). The said demand being both intermittent (one order every few days for a particular flight) and lumpy (a single order could fill up a flight, for example), it was an incredibly wicked problem.

Having had a rather unique career path in this “industry” I have, over the years, been exposed to a large number of unique “cases”. In 2012, I’d set about trying to identify patterns so that I could “productise” some of my work, but the ill-structured nature of problems I was taking up meant this simply wasn’t forthcoming. And I realise (after having read the above-linked tweetstorm) that I continue to learn from cases, and that I’m a much better data scientist than I was a year back, and much much better than I was two years back.

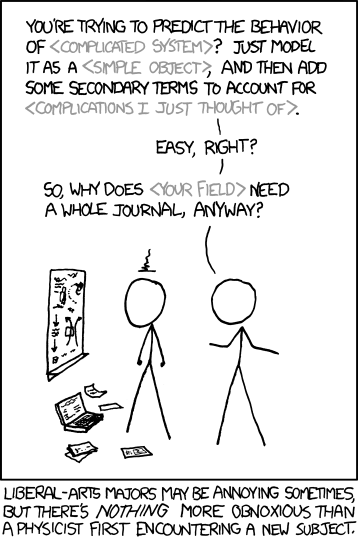

On the other hand, because data science attracts a lot of people from pure science and engineering (classically well-structured fields), you see a lot of people trying to apply overly academic or textbook approaches to problems that they see. As they try to divine problem patterns that don’t really exist, they fail to recognise novel “cases”. And so they don’t really learn from their experience.

Maybe this is why I keep saying that “in data science, years of experience and competence are not correlated”. However, fundamentally, that ought NOT to be the case.

This is also perhaps why a lot of data scientists, irrespective of their years of experience, continue to remain “junior” in their thinking.

PS: The last few paragraphs apply equally well to quantitative finance and economics as well. They are ill-structured professions that some practitioners (thanks to well-structured backgrounds) assume are well-structured.