When Gary Becker was awarded the “Nobel Prize” (or whatever its official name is) for Economics, the award didn’t cite any single work of his. Instead, as Justin Wolfers wrote in his obituary,

He was motivated by the belief that economics, taken seriously, could improve the human condition. He founded so many new fields of inquiry that the Nobel committee was forced to veer from the policy of awarding the prize for a specific piece of work, lauding him instead for “having extended the domain of microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behavior and interaction, including nonmarket behavior.”

Or as Matthew Yglesias put it in his obituary of Becker,

Becker is known not so much for one empirical finding or theoretical conjecture, as for a broad meta-insight that he applied in several areas and that is now so broadly used that many people probably don’t realize that it was invented relatively recently.

Becker’s idea, in essence, was that the basic toolkit of economic modeling could be applied to a wide range of issues beyond the narrow realm of explicitly “economic” behavior. Though many of Becker’s specific claims remain controversial or superseded by subsequent literature, the idea of exploring everyday life through a broadly economic lens has been enormously influential in the economics profession and has altered how other social sciences approach their issues

Essentially Becker sort of pioneered the idea of using economic reasoning for fields outside traditional economics. It wasn’t always popular – for example, his use of economics methods in sociology was controversial, and “traditional sociologists” didn’t like the encroachment into their field.

However, Becker’s ideas endured. It is common nowadays for economists to explore ideas traditionally considered outside the boundaries of “standard economics”.

I think this goes well beyond economics. I think there are several other fields that are prone to “go out of syllabus” – where concepts are generic enough that they can be applied to areas traditionally outside the fields.

One obvious candidate is mathematics – most mathematical problems come from “real life”, and only the purest of mathematicians don’t include an application from “real life” (well outside of mathematics) while writing a mathematical paper. Immediately coming to mind is the famous “Hall’s Marriage Theorem” from Graph Theory.

Speaking of Graph Theory, Computer Science is another candidate (especially the area of algorithms, which I sort of specialised in during my undergrad). I remember being thoroughly annoyed that papers and theses that would start so interestingly with a real-life problem would soon involve into inscrutable maths by the time you got to the second section. I remember my B.Tech. project (this was taken rather seriously at IIT Madras) being about what I had described as a “Party Hall Problem” (this was in Online Algorithms).

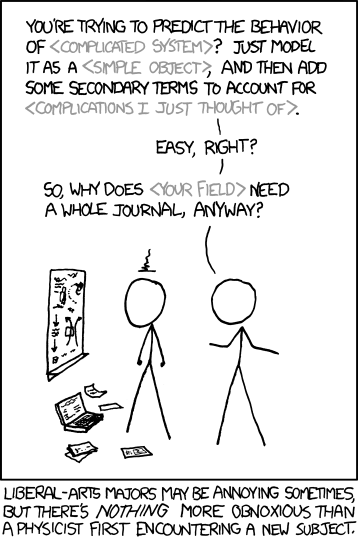

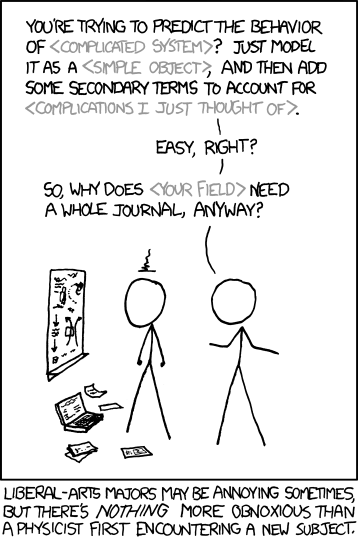

Rather surprisingly (to me), another area whose practitioners are fond of encroaching into other subjects is physics. This old XKCD sums it up

Complex Systems (do you know most complex systems scientists are physicists by training?) is another such field. There are more.

In any case, assuming no one else has done this already, I hereby christen all these fields (whose practitioners are prone to venturing into “out of syllabus matters”) as “Beckerian Disciplines” in honour of Gary Becker (OK I have a economics bias but I’m pretty sure there have been scientists well before Becker who have done this).

And then you have what I now call as “anti-Beckerian Disciplines” – areas that get pissed off that people from other fields are “invading their territory”. In Becker’s own case, the anti-Beckerian Discipline was Sociology.

When all university departments talk about “interdisciplinary research” what they really need is Beckerians. People who are able and willing to step out of the comfort zones of their own disciplines to lend a fresh pair of eyes (and a fresh perspective) to other disciplines.

The problem with this is that they can encounter an anti-Beckerian response from people trying to defend their own turf from “outside invasion”. This doesn’t help the cause of science (or research of any kind) but in general (well, a LOT of exceptions exist), academics can be a prickly and insecure bunch forever playing zero-sum status games.

With the covid-19 virus crisis, one set of anti-Beckerians who have emerged is epidemiologists. Epidemiology is a nice discipline in that it can be studied using graph theory, non-linear dynamics or (as I did earlier today) simple Bayesian maths or so many other frameworks that don’t need a degree in biology or medicine.

And epidemiologists are not happy (I’m not talking about my tweet specifically but this is a more general comment) that their turf is being invaded upon. “Listen to the experts”, they are saying, with the assumption that the experts in question here are them. People are resorting to credentialism. They’re adding “, PhD” to their names on twitter (a particularly shady credentialist practice IMHO). Questioning credentials and locus standi of people producing interesting analysis.

Enough of this rant. Since you’ve come all the way, I leave you with this particularly awesome blogpost by Tyler Cowen, who is a particularly Beckerian economist, about epidemiologists. Sample this:

Now, to close, I have a few rude questions that nobody else seems willing to ask, and I genuinely do not know the answers to these:

a. As a class of scientists, how much are epidemiologists paid? Is good or bad news better for their salaries?

b. How smart are they? What are their average GRE scores?

c. Are they hired into thick, liquid academic and institutional markets? And how meritocratic are those markets?

d. What is their overall track record on predictions, whether before or during this crisis?

e. On average, what is the political orientation of epidemiologists? And compared to other academics? Which social welfare function do they use when they make non-trivial recommendations?