Delivery aggregators are moving customer data away from the retailer, who now has less knowledge about his customer.

Ever since data collection and analysis became cheap (with cloud-based on-demand web servers and MapReduce), there have been attempts to collect as much data as possible and use it to do better business. I must admit to being part of this racket, too, as I try to convince potential clients to hire me so that I can tell them what to do with their data and how.

And one of the more popular areas where people have been trying to use data is in getting to “know their customer”. This is not a particularly new exercise – supermarkets, for example, have been offering loyalty cards so that they can correlate purchases across visits and get to know you better (as part of a consulting assignment, I once sat with my clients looking at a few supermarket bills. It was incredible how much we humans could infer about the customers by looking at those bills).

The recent tradition (after it has become possible to analyse large amounts of data) is to capture “loyalties” across several stores or brands, so that affinities can be tracked across them and customer can be understood better. Given data privacy issues, this has typically been done by third party agents, who then sell back the insights to the companies whose data they collect. An early example of this is Payback, which links activities on your ICICI Bank account with other products (telecom providers, retailers, etc.) to gain superior insights on what you are like.

Nowadays, with cookie farming on the web, this is more common, and you have sites that track your web cookies to figure out correlations between your activities, and thus infer your lifestyle, so that better advertisements can be targeted at you.

In the last two or three years, significant investments have been made by restaurants and retailers to install devices to get to know their customers better. Traditional retailers are being fitted with point-of-sale devices (provision of these devices is a highly fragmented market). Restaurants are trying to introduce loyalty schemes (again a highly fragmented market). This is all an attempt to better get to know the customer. Except that middlemen are ruining it.

I’ve written a fair bit on middleman apps such as Grofers or Swiggy. They are basically delivery apps, which pick up goods for you from a store and deliver it to your place. A useful service, though as I suggest in my posts linked above, probably overvalued. As the share of a restaurant or store’s business goes to such intermediaries, though, there is another threat to the restaurant – lack of customer data.

When Grofers buys my groceries from my nearby store, it is unlikely to tell the store who it is buying for. Similarly when Swiggy buys my food from a restaurant. This means loyalty schemes of these sellers will go for a toss. Of course not offering the same loyalty program to delivery companies is a no-brainer. But what the sellers are also missing out on is the customer data that they would have otherwise captured (had they sold directly to the customer).

A good thing about Grofers or Swiggy is that they’ve hit the market at a time when sellers are yet to fully realise the benefits of capturing customer data, so they may be able to capture such data for cheap, and maybe sell it back to their seller clients. Yet, if you are a retailer who is selling to such aggregators and you value your customer data, make sure you get your pound of flesh from these guys.

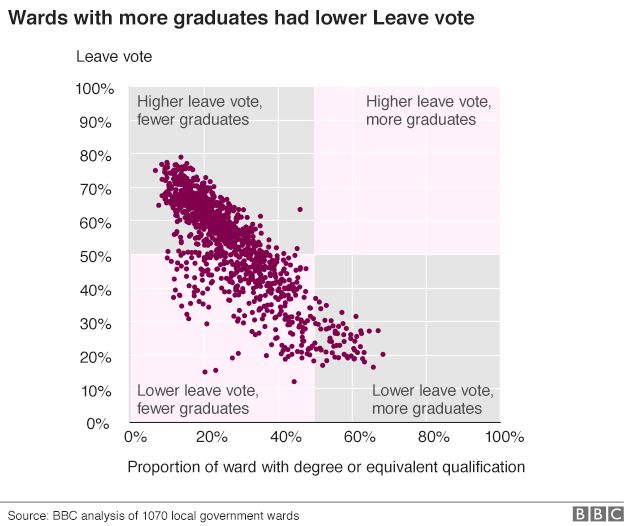

next to the line, to show the extent of correlation!