Quartz reports that restaurant reservations have been taken over by bots in San Francisco. Certain restaurants in that city are incredibly hard to get reservations at, so people have started letting lose bots that check for availability every minute and grab the table as soon as it’s available. In fact, there are enough bots out there that at a particular restaurant which opens reservations at 4 am, all tables are taken by 4:01. Every day.

In Kannada, there is an idiom that says “gubbi mEle brahmAstra”, which means using the weapon of Brahma (widely recognized in Hindu epics are the most powerful weapon) to annihilate a sparrow. Using a bot for restaurant reservations is a solution that falls under this category. However, that someone had to think up of this solution shows that there is something wrong with the restaurant reservation market. And it is not just in San Francisco (I guess this solution was first implemented there thanks to the penetration of online restaurant reservations and the high number of techies in the city. Bangalore fails on the first count).

The problem with the way restaurant reservations currently work is that the option is priced at zero. And thus gets allocated on a first come first served basis. Suppose I want to go out on a date tonight but am not sure what cuisine my wife is craving today. Anticipating crowds, given that it is a Saturday, I will make reservations in four different restaurants serving four different cuisines. There is nothing that currently prevents me from doing that. And it costs me nothing (apart from the cost of four phone calls).

A restaurant reservation is essentially an option to occupy a table of a certain size at a certain restaurant in a particular time period. If you show up at the restaurant at the appointed time, the restaurant is obliged to offer you a table. However, the way it is currently implemented is that you are not obliged to show up at that restaurant at that particular time. If you don’t show up, the table the restaurant had “reserved” for you will go empty for that evening, thus resulting in loss of business.

How can a restaurant handle this? One idea is to overbook. If you have 10 tables, allow 12 people to make reservations, in the hope that on an average day, 10 or less will show up. While this may lead to higher occupancy, problem is when all 12 show up. You then run the reputational risk of making a reserved guest wait, or worse, turning them away. Another option is to book only a fraction of the tables. If you have 10 tables, give out reservations only for 8, and let people know that you are open to walkins (if someone calls after the 8 are taken, you can say “I’m sorry, but we can’t take any reservations. However, we have some unreserved tables. You can come and check it out. If you’re lucky you’ll get it”). That way, by keeping yourself open for walkins, you can prevent loss of inventory- except that if you are a high end restaurant you are unlikely to get too many walk in customers.

Another option (which I believe is a method online retailers in India use for cash-on-delivery customers) is to maintain a list of people who called you along with their phone numbers and whether they showed up. That way, you can deny habitual offenders a reservation. However, considering that if you are a high end restaurant people are unlikely to visit you very often this may not work either.

The ideal economic solution, of course, would be to charge for reservations. People pay a small deposit when they make a reservation. If they do show up, this amount gets adjusted against their bill. However, given that most reservations happen over the phone (except in SF), you have no way to charge for it. So is the solution that you move your reservations exclusively online, so that you can charge for it? Then you could lose out on customers who are uncomfortable with making reservations online.

Even if all your reservations were online (like in SF), there is a problem in charging for reservations – you wouldn’t want to be the first restaurant doing that. One thing high end restaurants pride themselves on is their reputation, and charging for reservations can make them appear “cheap”, and they wouldn’t want to do that unless it is the done thing.

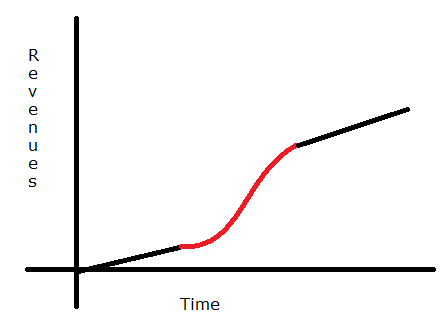

So how are restaurants managing the situation now? My take is that they are adjusting for it in the price. They are not overbooking, but assuming the cost of empty tables (as a result of no shows) in their overall pricing. This way, customers who are honouring reservations are effectively subsidizing those that don’t. While the market “clears”, the implicit subsidy towards customers who don’t honour their reservations leads to dead weight loss. There is also moral hazard – since desirable customers (the ones who show up) are subsidizing the un-desirable (the ones that don’t).

Is there a solution to this? One way to look at this would be for restaurants to centralize their reservations. I’m surprised no one has done it yet. You can have a website and a call centre from which you can take reservations for a large number of restaurants. The restaurants will pay for it since it will mean that they don’t need to have someone by the phone taking and managing reservations. And given that the same call centre manages bookings for multiple restaurants, they can identify duplicate bookings and overbook accordingly. Customers can be incentivized to use the same ID for booking for multiple restaurants by introducing a multi-restaurant loyalty card. And then – once there is a large number of restaurants that have moved their reservations to this call centre, they can start thinking of collectively moving towards a system of penalizing for unfulfilled reservations.

There – I’m giving a business idea away for free!