The IDFC-Duke-Chicago survey that concluded that 50% of Bangalore had covid-19 in late June only surveyed 69 people in the city.

When it comes to most things in life, the answer is 42. However, if you are trying to rationalise the IDFC-Duke-Chicago survey that found that over 50% of people in Bangalore had had covid-19 by end-June, then the answer is not 42. It is 69.

For that is the sample size that the survey used in Bangalore.

Initially I had missed this as well. However, this evening I attended half of a webinar where some of the authors of the survey spoke about the survey and the paper, and there they let the penny drop. And then I found – it’s in one small table in the paper.

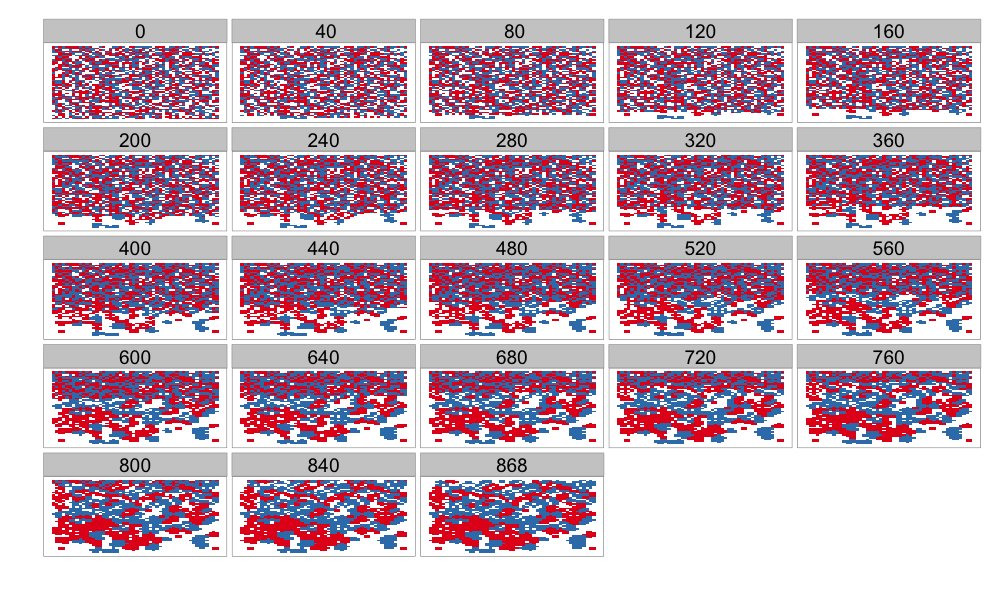

The above is the table in its glorious full size. It takes effort to read the numbers. Look at the second last line. In Bangalore Urban, the ELISA results (for antibodies) were available for only 69 people.

And if you look at the appendix, you find that 52.5% of respondents in Bangalore had antibodies to covid-19 (that is 36 people). So in late June, they surveyed 69 people and found that 36 had antibodies for covid-19. That’s it.

To their credit, they didn’t highlight this result (I sort of dug through their paper to find these numbers and call the survey into question). And they mentioned in tonight’s webinar as well that their objective was to get an idea of the prevalence in the state, and not just in one particular region (even if it be as important as Bangalore).

That said, two things that they said during the webinar in defence of the paper that I thought I should point out here.

First, Anu Acharya of MapMyGenome (also a co-author of the survey) said “people have said that a lot of people we approached refused consent to be surveyed. That’s a standard of all surveying”. That’s absolutely correct. In any random survey, you will always have an implicit bias because the sort of people who will refuse to get surveyed will show a pattern.

However, in this particular case, the point to note is the extremely high number of people who refused to be surveyed – over half the households in the panel refused to be surveyed, and in a further quarter of the panel households, the identified person refused to be surveyed (despite the family giving clearance).

One of the things with covid-19 in India is that in the early days of the pandemic, anyone found having the disease would be force-hospitalised. I had said back then (not sure where) that hospitalising asymptomatic people was similar to the “precogs” in Minority Report – you confine the people because they MIGHT INFECT OTHERS.

For this reason, people didn’t want to get tested for covid-19. If you accidentally tested positive, you would be institutionalised for a week or two (and be made to pay for it, if you demanded a private hospital). Rather, unless you had clear symptoms or were ill, you were afraid of being tested for covid-19 (whether RT-PCR or antibodies, a “representative sample” won’t understand).

However, if you had already got covid-19 and “served your sentence”, you would be far less likely to be “afraid of being tested”. This, in conjunction with the rather high proportion of the panel that refused to get tested, suggests that there was a clear bias in the sample. And since the numbers for Bangalore clearly don’t make sense, it lends credence to the sampling bias.

And sample size apart, there is nothing Bangalore-specific about this bias (apart from that in some parts of the state, the survey happened after people had sort of lost their fear of testing). This further suggests that overall state numbers are also an overestimate (which fits in with my conclusion in the previous blogpost).

The other thing that was mentioned in the webinar that sort of cracked me up was the reason why the sample size was so low in Bangalore – a lockdown got announced while the survey was on, and the sampling team fled. In today’s webinar, the paper authors went off on a rant about how surveying should be classified as an “essential activity”.

In any case, none of this matters. All that matters is that 69 is the answer.