Ok this is the sort of speculative predictive post that I don’t usually indulge in. However, I think my blog is at the right level of obscurity that makes it conducive for making speculative predictions. It is not popular enough that enough people will remember this prediction in case this doesn’t come through. And it’s not that obscure as well – in case it does come through, I can claim credit.

So my claim is that companies whose work doesn’t involve physically making stuff haven’t explored the possibilities of remote work enough before the current (covid-19) crisis hit. With the gatherings of large people, especially in air-conditioned spaces being strongly discouraged, companies that hadn’t given remote working enough thought are being forced to consider the opportunity now.

My prediction is that once the crisis over and things go back to “normal”, there will be converts. Organisations and teams and individuals who had never before thought that working from home would have taken enough of a liking to the concept to give it a better try. Companies will become more open to remote working, having seen the benefits (or lack of costs) of it in the period of the crisis. People will commute less. They will travel less (at least for work purposes). This is going to have a major impact on the economy, and on cities.

My prediction is that once the crisis over and things go back to “normal”, there will be converts. Organisations and teams and individuals who had never before thought that working from home would have taken enough of a liking to the concept to give it a better try. Companies will become more open to remote working, having seen the benefits (or lack of costs) of it in the period of the crisis. People will commute less. They will travel less (at least for work purposes). This is going to have a major impact on the economy, and on cities.

I’m still not done with cities.

For most of history, there has always been a sort of natural upper limit to urbanisation, in the form of disease. Before germ theory became a thing, and vaccinations and cures came about for a lot of common illnesses, it was routine for epidemics to rage through cities from time to time, thus decimating their population. As a consequence, people didn’t live in cities if they could help it.

Over the last hundred years or so (after the “Spanish” flu of 1918), medicine has made sufficient progress that we haven’t seen such disease or epidemics (maybe until now). And so the network effect of cities has far outweighed the problem of living in close proximity to lots of other people.

Especially in the last 30 years or so, as “knowledge work” has formed a larger part of the economies, a disproportionate part of the economic growth (and population growth) has been in large cities. Across the world – Mumbai, Bangalore, London, the Bay Area – a large part of the growth has come in large urban agglomerations.

One impact of this has been a rapid rise in property prices in such cities – it is in the same period that these cities have become virtually unaffordable for the young to buy houses in. The existing large size and rapid growth contribute to this.

Now that we have a scary epidemic around us, which is likely to spread far more in dense urban agglomerations, I imagine people at the margin to reconsider their decisions to live in large cities. If they can help it, they might try to move to smaller towns or suburbs. And the rise of remote work will aid this – if you hardly go to office and it doesn’t really matter where you live, do you want to live in a crowded city with a high chance of being hit by a stray virus?

This won’t be a drastic movement, but I see a marginal redistribution of population in the next decade away from the largest cities, and in favour of smaller towns and cities.It won’t be large, but significant enough to have an impact on property prices. The bull run we’ve seen in property prices, especially in large and fast-growing cities, is likely to see some corrections. Property holders in smaller cities that aren’t too unpleasant to live in can expect some appreciation.

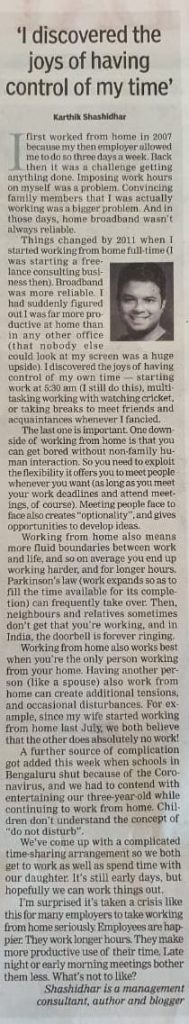

Oh, and speaking of remote work, I have an article in today’s Times Of India about the joys of working from home. It’s not yet available online, so I’ve attached a clipping.