I was never a big fan of “brainstorming”. I’m referring to those meetings where everyone gets together and thinks aloud, in order to converge to a solution. In the past, when I’ve been involved in such exercises, they’ve mostly come to nothing, and mostly ended with a list of to-dos which got never done (this was mostly in a corporate context). As a consequence, I started hating large meetings also (either most people wouldn’t add value or it would end up like a group discussion with everyone shouting), and have been trying to avoid them.

This time, though, it was different. The context was not corporate. The agenda did not involve an item of day to day work. None of us had a firm stand on the topic at the beginning of the meeting, with each of us having our own apprehensions of either stand (when people come with preconceived ideas and biases, there usually is nothing to storm our brains about).

And so we got together. And we talked. There were times when no one spoke. There were times when it actually turned out to be like a group discussion (I actually said, “ok I have ten points which I haven’t been able to make in the last one hour. I’ve written them down and let me shoot now”). But the situation never got out of hand. Mutual respect meant that cross-talk quickly died out, and we listened to each other. And it was extremely civil.

And then things started crystallising. Soon, some of us had an opinion. Later, others did. Some were ultimately not convinced, but had an opinion anyway. In a period of about twenty minutes somewhere in the third hour of the session, we all seemed to have an “aha moment” (apologies for that consultantspeak). But such moments occurred at different times for each of us.

And then we did the usual thing of “going round the table” for each of us to express our opinions. And then we did. And as each of us expressed our opinions, we discussed it further. Things crystallised better. And we ended the meeting asking everyone who was there to blog about it.

This is what I wrote:

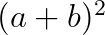

given that these two internets are independent, the total value is  . Now, if we were to tear down the walls, and combine the two internets into one, what will be the total value? Now that we have one network of

. Now, if we were to tear down the walls, and combine the two internets into one, what will be the total value? Now that we have one network of  users, the value of the network is

users, the value of the network is  or

or  . So what is the additional benefit that we can get by imposing net neutrality, which means that we will have one internet?

. So what is the additional benefit that we can get by imposing net neutrality, which means that we will have one internet?  , of course!

, of course!

This is what Nitin wrote:

If the government opens up the telecom service market to greater competition, perhaps by issuing unlimited licenses, then there is a case to allow them the freedom to discriminate among customers. As the state-owned carrier, BSNL can provide a neutral internet. However, if the government does not open the sector to further competition, therefore shielding the telecom service providers from more competition, then mandating net neutrality provides a reasonable approach to promoting the public interest.

Varun wrote this:

the regulator’s two major tasks are to enhance social welfare by protecting the consumer interest and to create an environment that is conducive for business — that will further enhance social welfare. A neutral internet will definitely benefit the consumers interest; but since the regulatory framework is not conducive for business, it appears that net-neutrality is in conflict with business interests. The situation can change if the regulatory framework is eased and the markets are opened up.

And Pranay wrote this:

net neutrality as a principle must be upheld. This is because communication network providers should not have the unfair advantage of being able to price internet content differently. Once the communication networks are setup, costs do not change with consumers accessing different content. In any case, the communication service providers are free to have fair internet usage policies to prevent induced demand effects

Gautam went down approximately the same path as me, and wrote this:

This is exactly why I oppose Zero Rating as well, whether paid or unpaid – it tends towards creating pockets of disconnected users per telecom company and while this is valuable for the telecom company and the applications and sites that are zero-rated, it reduces the total utility of the public internet, as a whole.

Devika deviated a bit from the crowd. This is what she said:

That said, it does not mean that ISPs should be restricted from entering into contracts with content providers. If Flipkart wants to undertake a joint marketing initiative with Bharti Airtel, it should be allowed to so. For example, Flipkart can give benefits to Airtel from sharing their customer base. To be extremely clear, such collaborations should not hinder access to any other internet sites. This will maintain a level playing field for all content providers.

Anupam, too, differed, and argued that customers need to be given choice:

If a person runs his business solely based on international VoIP calls and doesn’t mind paying extra for ensuring reliability and speed, he should be able to access that privilege. Or, for that matter, a Facebook or Twitter addict who wants these apps to be quick such that they can post real time selfies, should be able to choose these apps over say, apps which give real time updates on political happening in Nicaragua. Thus, people can be given a choice as to which data packets have to be prioritized within their limited bandwidth

And Pavan argued that competition is alone not sufficient:

However, if the internet is a public good – will competition ever be sufficient to ensure the vibrancy of the network? Will competition be sufficient to improve the effective network size? I would argue that it might fall short of the mark. Thus, regulations that enforce net neutrality may be necessary to prevent ‘walled gardens’ from springing up.

As you can see, our opinions at the end of the meetings all differ. But you can also see that the posts are all well-argued, implying that at the end of the meeting we all had a reasonable degree of clarity. And that is what made it a brilliant brainstorming session.

Now if only all other brainstorming sessions were to be as good! Oh, and it’s a long post already but here are some #learnings on what makes for a successful brainstorming session:

- Open minds on behalf of participants

- Mutual respect, and giving everyone a chance to speak

- No overbearing participants or moderators, leading to a freewheeling debate

As you can see, all these are similar to what makes a multiplayer gencu successful! But brainstorming has a specific agenda, so it’s not a gencu!