In India, officially, sports betting is illegal. Of course, there are lots of “underground” betting networks which we will not go into here. This post, instead, is about a different kind of “betting” on sports.

I’ve long maintained that Mahendra Singh Dhoni is grossly overrated as a cricket captain. While he did win that ICC World T20 in 2007 (back then his captaincy was pretty good), since then he’s shown himself to be too conservative as a captain. In that sense, I’m glad he retired from Tests (thus relinquishing captaincy as well) in 2014, paving the way for the more aggressive Virat Kohli to lead.

Even in limited overs games, I’ve maintained that while in the past he’s been instrumental in orchestrating chases, that ability is now on the wane, with last night’s choke being the latest example of him botching a chase. Earlier this year as well, he choked a chase in Zimbabwe. There are more such examples from the IPL as well.

Given last night’s fuck-up, I think it’s a great time to replace him as captain for limited overs games. I’m not hopeful of this happening, though, and this is in part due to the “betting at another level” that happens in elite sport.

Back in 2011 or 2012, a hashtag called #SachinRetire started making the rounds on Twitter. The context was that with the 2011 world cup having been won, it was a great opportunity for Sachin Tendulkar to retire on a high note. He continued playing on, though, in the hope of hitting “100 100s in international cricket”, the result of which was mostly mediocre cricket on his part.

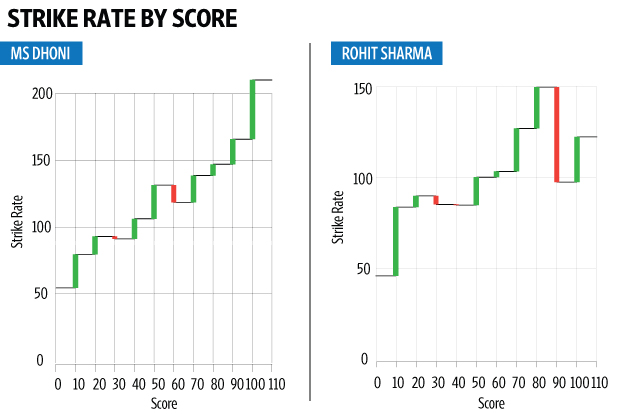

Tendulkar’s 100th 100 finally came a year after his 99th, in an Asia Cup match against Bangladesh. He scored at a strike rate of 78, in a match India lost. A lot of the blame for the loss can be put on his slow rate of scoring, and consequently, on the 100th 100 hype.

It was another good opportunity to retire, but he continued playing, until a special Test series was organised in 2013 so that he could retire “at home”.

The dope in sports circles in those days was that while Tendulkar himself was keen to go, there were plenty of endorsements he was involved in, and those sponsors would have had to take a loss if he retired. Thus, the grapevine went, he had to take his sponsors into confidence and “prepare them” in order to choose an opportune time to retire.

Endorsements and sponsorships are the “other kind of betting” I mentioned earlier in the post. As soon as a sportsperson “makes it”, there is a clutch of brands who wants to cash in on his popularity by asking him to endorse them. The money involved makes it a good deal for the sportsperson as well.

By choosing to sponsor a sportsperson and getting him to endorse their brand, sponsors are effectively taking a bet on the player’s career – the better the player’s career goes, the greater the benefit for the brand from the sponsorship deal. In case the player’s career stalls, or he is caught in a scandal, the brand also suffers by association (think Tiger Woods or Maria Sharapova).

The concern with betting on sports in India is that bettors might try to influence the results of matches they’ve bet on, by possibly fixing them. This, along with “protecting the poor punter” are reasons why betting on sports is banned in India.

The problem, however, is that with this “other kind of betting” (sponsorships), the size and influence of the bettors (sponsors) means that there is a greater chance of the bettors seeking to influence the results of their investments.

A sponsor, for example, will not be happy if their “sponsee” is left out of his team, for whatever reason. Any negative impact on the sponsee’s career, from being dropped, to being demoted from captaincy to being sold to a “lesser club” negatively affects the brand value of the sponsor (by association).

And so, in cases where it’s possible (I can’t imagine a sponsor trying to influence Jose Mourinho’s decision, for example), the sponsor will try to influence selection decisions where it might benefit them. So Tendulkar’s sponsors will lobby with selectors to keep him in the team. Dhoni’s sponsors will lobby to keep him as captain. And so forth.

I’m not advocating that some kind of regulation be brought in to curb sponsors’ influence – any such regulation can only be counterproductive. All I’m saying is that betting already exists in Indian cricket, except that rather than betting on matches, bettors are betting on players! And so there is no real argument to ban “real” sports betting in India.

At least in that case, sponsors will be able to hedge their investments in the market rather than seeking to influence the powers behind the sport!