With the resignation of Infosys President BG Srinivas and the subsequent drop in the share price in the markets today, the NR Narayana Murthy premium on the Infosys stock is over. Ironically, this happens almost exactly a year since NRN made a comeback to the company in an executive capacity.

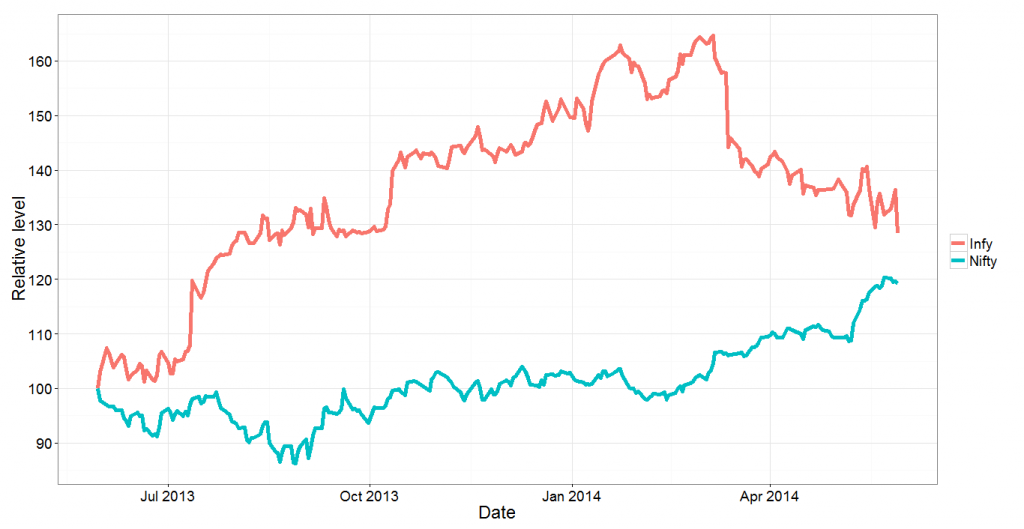

The figure below charts how the Infosys stock and the market index (Nifty ) have moved in the last one year. In order to compare the two, we have indexed their prices as of 30th May 2013, just before NRN’s return was announced (the announcement was made as of 2nd June, but the sharp spike in Infy on 31st May 2013, when the broad market fell, can be attributed to insider trading by people in the know), to 100. Notice how the Infosys stock soared in the six months after NRN’s return. In January and February, the stock traded at a 60% premium to its pre-NRN value, while the nifty was practically flat till then.

And then things started dropping. Even when the broad markets rose in March-April this year, Infosys continued to fall. The rally in early-mid May took it along, but now the stock has fallen again. This morning (latest data as of noon), the stock has fallen by about 6% thanks to Srinivas’s departure, and we can see that the gap between Infy and the market has really narrowed.

Next, we look at the ratio of the Infy price to the market index. Again we index it to 100 as of 30th May 2013. This graph shows the premium in the Infy share price over the last year. Notice that for the first time, the premium has fallen below 10% (it’s currently 7%).

Finally, we will compare the Infy stock to the CNX IT index, which tracks the sector (that way, any sectoral premium in Infy can be extracted out). Again, we will plot the relative values of Infy to the CNX IT index, indexed to 100 as of 30th May 2013.

This graph looks like no other. What this tells us is that whatever premium Infosys enjoys over the broad market is a function of the sector, and that ever since the sharp drop in early March (on account of weak results), the NRN premium on the Infy stock relative to the sector has disappeared. As of now, compared to the sector, Infy is at an all time low.

Finally, a regression. If we regress infy stock returns against the returns in the IT index and Nifty, what we find is that Nifty returns hardly affect Infosys returns (R^2 of 7%), while the IT Index returns explain about 76% of Nifty returns. When regressed against both, Nifty returns come out as insignificant and the R^2 remains at 76%.

Putting all these statistics aside, however, the message is simple – the NRN premium on the Infy stock is over.